Kolakkad native M R Albert (73) committed suicide in Kerala on the day after the national Milk day. He had served as the president of Kolakkad Dairy Co-operative Society for 25 years.

He had to give his life because of a paltry Rs 2 lakh loan from Kannur District Co-operative Bank.

How much does a personal loan of Rs 200000 costs at say 9% interest for 5 years ?

It is Rs 4152.00 per month. Can we really think of a situation wherein a dairy farmer from the world’s largest milk producing country commits suicide for a financial liability of Rs 4152 per month.

Farmer suicides are on the rise in Kerala. On November 10, a farmer named K G Prasad from Alappuzha’s Thakazhy died after consuming poison. In his suicide note, he blamed the government for leaving him in debt. A few days after Prasad’s suicide, Thomas alias Joy, a dairy farmer in Wayanad found hanging from a tree. His relatives said that he had accumulated a debt of over Rs 10 lakh.

What does the government do to the corporate debtors?

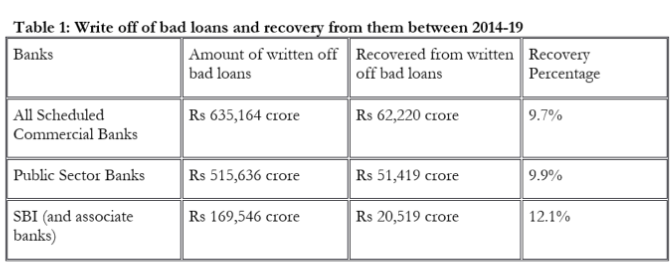

Between 2014 and 2019, Indian scheduled commercial banks wrote off bad loans totalling Rs 6.35 lakh crore, recovering only 9.7% (Rs 62,220 crore) from the written-off amount, according to an RTI response from the Reserve Bank of India.

In the broader period from 2004 to 2019, banks wrote off Rs 8.41 lakh crore in bad loans, with 75% of this, Rs 6.35 lakh crore, occurring in the last five years. This practice of writing off loans, primarily to corporates, has been criticized as a scam, as former RBI Deputy Governor K C Chakrabarty highlights.

The government’s claim of reduced bad loans is largely attributed to write-offs rather than actual recovery efforts by the banks. Gross NPAs declined from 11.5% in 2018 to 9.3% in 2019, but this is more reflective of writing off bad loans than genuine recovery achievements.

What does the government data says ?

The table retrieved through RTI clearly expose the government’s deceptive assertions that “write off does not mean waiver, borrowers do not get benefitted from write offs, banks continue to recover those loans” as untrue.

What is value of life in a capitalistic world ?

Let me illustrate by sharing the famous Ford’s Pinto case here

What is the value of a life? The moral dilemma of putting a price on human life challenges us, transcending mere currency. Unfortunately, history reveals instances where lives were quantified in dollars, as seen with the Ford Pinto in the 1970s. The car’s flawed design led to fatal consequences, prompting internal discussions at Ford.

Rectifying the fuel tank issue would cost $11 per Pinto, totalling $121 million for 11 million cars. Conversely, Ford projected a $70 million saving by avoiding a recall, basing calculations on potential accidents and settlements. This highlights a disturbing juxtaposition of financial considerations against human safety.

Utilitarian Logic

Presently, entities frequently employ Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian logic, known as cost-benefit analysis. Utilitarianism, advocating that the morally right action maximizes overall good, has various interpretations. Professor Sandel of Harvard Business School raises probing questions, such as whether we should prioritize the happiness of a potentially cruel majority and if all values can be quantified and compared using a common measure like money.

Farmers are being sacrificed in the name of benefiting business communities. The government seems to value the lives of 1.25 farmers and farm laborers per hour as insignificant compared to the interests of large business houses.

India leads the world in Farmer’s suicide

Farmers’ suicides in the U.S. have risen since the 1980s, with over 1,500 Midwest farmers taking their lives. This mirrors a global crisis: in Australia, a farmer dies by suicide every four days; in the UK, one farmer a week takes their own life, and in France, it is one every two days. Since 1995, more than 270,000 farmers in India have died by suicide.

In India, farmer suicides, stemming from the inability to repay loans, have been prevalent since the 1970s. NCRB data reveals sustained high numbers from 2014 to 2020, with 5,600 farmers ending their lives in 2014 and 5,500 in 2020. Including agricultural laborers in 2020, the total suicides surpass 10,600.

India, with 70% reliant on agriculture, had agriculture contributing 15.4% to its economy in 2017. In 2020, 41.49% of the workforce was linked to agriculture. Farmer suicides constitute 11.2% of all suicides, attributed to various factors. Between 2013 and 2019, farmers’ income rose by 30%, but debt surged by 58%, causing their debt as a percentage of annual income to increase by 13 points, as per Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation data.

Data Distortion

In response to Sh Kesinini Srinivasan MP, the agriculture minister shared depressing details regarding the data collection for farmer suicides. He informed the parliament that the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) under the Ministry of Home Affairs compiles and disseminates this information in its publication titled ‘Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India’ (ADSI).

Reports up to 2021 are available on the NCRB website (https://ncrb.gov.in). However, the NCRB does not provide separate data on tenant farmers’ suicides or specify distinct reasons for farmers’ suicides in its ADSI Reports. Is this a correct approach of not capturing and publishing data on labourer suicide also along with farmers ? Is it also justifiable to not to specify distinct reasons for such suicides? Doesn’t it portray a window dressing to keep the numbers of farmers suicides shared at almost half the values in public domain?

This reminds me of a famous quote by Ruth Dreifuss;

“Poverty doesn’t shame the people who are affected by it, Poverty shames society.“

It is time for me to conclude my case in front of all stakeholders. I always took pride in stating that a farmer engaged in backyard farming never resorted to suicide. Today, this perception has been shattered.

I find it unbelievable that our system failed to empathize with Albert, who dedicated over 25 years as the president of a dairy cooperative.

There is a pressing need for a paradigm shift in our approach to designing financial instruments for farmers. Farm produce serves as their sole income to repay loans, and climate change disrupts their cash flow cycles. Farmers deserve more legitimacy in obtaining credit guarantees and collateral-free loans. Their self-esteem is their primary asset, and they would rather face the consequences than default on a loan.

It is high time for policymakers to translate their words into action. I invite your comments on how we can put an end to farmers’ suicides resulting from financial distress.

Source : Dairy blog by Kuldeep Sharma Chief editor dairynews7x7.site