Gujarat’s Amul has courted controversy as a ‘challenger’ to Karnataka’s homegrown Nandini, but the dairy giant is struggling due to rising costs, farms shutting down.

The arrival of Gujarat-based dairy juggernaut Amul in Karnataka has caused a political firestorm over an alleged BJP “conspiracy” to wipe out local brand Nandini and flood the market with pricier milk. However, despite its size and reputation, Amul is grappling with major inflation-related challenges in Gujarat, and is now mulling developing gomutra (cow urine) and gobar (dung) products to help manage costs and provide incentives to producers.

ThePrint visited Gujarat’s Anand and Kaira (earlier Kheda) districts, the hubs of the state’s dairy industry, to find out the reasons for escalating prices and the issues confronting Amul, the iconic brand of the state government’s Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF).

Dairy industry insiders said that many private milk farms with 300-400 cattle are shutting down, while smaller producers who have a dozen or less cows are battling for survival amid mounting green fodder prices.

Further, Amul is currently struggling to keep its demand-supply network intact across India in the face of soaring energy, labour, and transportation costs.

Meanwhile, the milk cooperative industry in Gujarat is witnessing at least two to three price revisions annually, leading to around a 10 per cent hike in milk prices in the past year and a half. Simultaneously, milk producers are clamouring for more returns, exacerbating the already challenging situation.

Notably, the organisation — which includes 18,600 cooperative societies in villages and 18 member unions spread across 33 districts — is now largely controlled by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The chairpersons of apex body GCMFF as well as all the district unions are BJP leaders, most of them MLAs.

Acknowledging that Amul is facing challenges due to inflation, Shankar Chaudhary, the Speaker of the Gujarat Legislative Assembly and the chairperson of Banas Dairy, one of the 18 member unions, said diversification could help minimise the impact.

“Amul is trying to find ways out of the inflation by marketing gau mutra and gobar products, including biogas, cow-urine powders, and so on,” Chaudhary claimed.

Successful yet struggling

Gujarat’s Anand Milk Union Limited (Amul) is well-known as one of the greatest success stories of India’s pre-independence cooperative movement, starting out in 1946 with two village cooperatives and 247 litres of milk production on its first day.

A lot of milk has flowed under the bridge since then.

The Anand unit currently has 1,240 village direct cooperatives (VDCs) from where Amul procures milk. The first Amul headquarters here now has a swanky office and cutting-edge operating systems that track producers, cattle, milk production, agents, dealers, and all business data in a click from the managing director’s office.

The organisation registered a turnover of Rs 55,000 crore in the last financial year to which the Anand unit had contributed 11,750 crore, said Amit Vyas, managing director of Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers’ Union, popularly known as Amul Dairy.

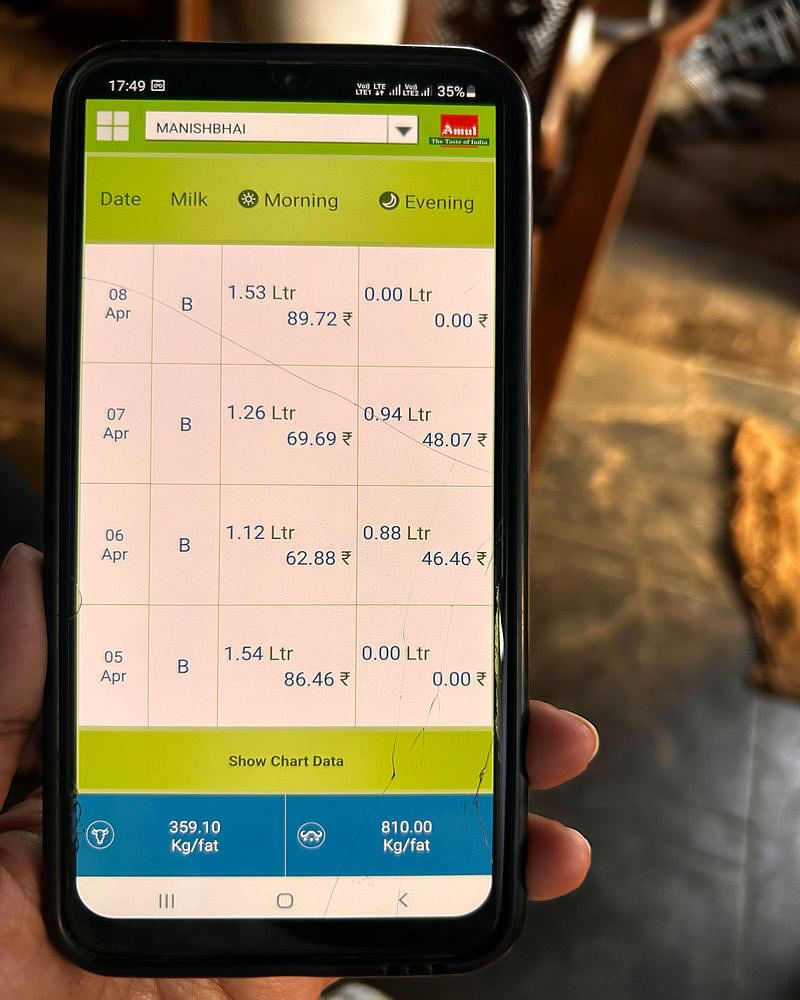

The cooperative has an app installed in every milk producer’s phone to minimise leakage in the supply system, making tracking network almost foolproof, he added.

“In this cooperative structure, 83 per cent of our earnings go to the milk producers. This is the highest payback among any form of cooperatives in the country. Rest of the 17 per cent is spent towards labour, energy, transportation, packaging, and maintenance of the entire-top-to ground mechanism that we have built,” Vyas said.

“It is almost unsustainable,” he noted, “but Amul’s network is resilient enough to weather all storms.”

The biggest such ‘storm’ in Gujarat has been inflation, trumping even the impact of Covid restrictions and outbreaks of lumpy cow disease, dairy insiders told ThePrint. The result has been rising prices.

“In the last financial year, the energy cost has gone up by 46 per cent and the transportation cost has risen by 6 per cent. We have also got letters from the government announcing revision in the labour cost. We have to factor in all these costs and are left with no option other than price revision,” Vyas said.

According to the latest available price data from the Department of Consumer Affairs, the average price of 1 litre of milk rose 10.5 per cent to Rs 56.8 on 4 April, 2023, from Rs 51.4 a year earlier.

This rise in prices is not linked to profit-making, said Brig Vinod Bajiya, executive director of Banas Dairy, which has 1,750 VDCs under it.

“Milk production is not a profitable business. It is a requirement. People need to understand this. Amul is not a corporation but a cooperative. It is the only cooperative in the country that has made it a nationally and even internationally known brand,” Bajiya told ThePrint.

“Amul survived and still sustains due to the network it has built and because people are contributing on the ground. Banas Dairy has 900 tankers on the road at any point of time ferrying milk,” he added.

Solutions in play, ‘sexed semen’ to cow urine R&D

To increase the supply of milk and stabilise prices, Amul is using various reproductive technologies for cows.

These, Bajiya said, include “sexed semen” technology, which allows for sex-selective breeding, in order for cows to give birth to female calves.

“Lumpy skin disease impacted milk production by 4 to 5 per cent, but we vaccinated fast. Now, we have 250 veterinary doctors on payroll to support the cattle and to minimise the burden on producers,” he added.

Banas Dairy chairman and BJP leader Shankar Chaudhury said that the organisation is also trying to tap into other cow products to help manage costs.

“The cattle economy has traditionally been very resilient and India has survived on it for years,” he said. “The soil needs manure for farming, and that comes from cow dung. It is used to produce biogas too. There are R&D processes running to extract powder from cow urine, which has medicinal values. We will procure these from the farmers too, and give them an incentive,” he added.

On the ground, however, dairy farmers and investors are now growing increasingly restive in the face of falling profits.

‘Producers not gaining from price revisions’

Out of approximately 110 big milk producing farms in the Anand-Kaira zone, about half have closed down over the past two or three years due to a lack of profitability, said a senior official of the cooperative. These farms, he added, were largely owned by wealthy businesspersons and non-resident Indians (NRIs).

The official, however, claimed that even though such farms “invested crores” they “did not put in the required effort to rear cattle”. Instead, he emphasised the importance of smaller players.

“Amul is meant for the small and marginal producers and they make the cooperative run successfully,” the official said.

Meanwhile, dairy farmers/owners that ThePrint spoke to claimed they had invested plenty of effort and money, but were struggling to stay afloat in the midst of rising prices of cattle feed and green fodder.

“The prices of cattle feed and green fodder are soaring. Even after price revision, the producers do not make any gains,” said Sanjay Rabari, the owner of Shibam Dairy in Anand’s Gopalpura village.

He has 400 cattle and his farm produces 3,000 litres per day, but business has been bad for three years, he claimed. “I invested Rs 11 crore in building the plant and installing cutting-edge technology. But, now I can barely pay the EMIs. Many of our community members have shut down,” Rabari said.

Apart from price rise, Rabari blamed “duplicate” and unbranded milk for the crisis. “There are middlemen who collect milk from the farmers at a higher price, and sell it off at a cheaper price,” he alleged. “This is unsterilised, unprocessed milk with artificial fat, not fit for consumption. There should be regulatory actions against them.”

Meanwhile, Manish Thakur, a small-scale milk producer at Jitodia cooperative in Anand, claimed he could barely make ends meet. The family owns four cows and three buffaloes that collectively yield about 20 litres of milk daily. Once costs are factored in, the earnings are paltry.

“We earn Rs 30,000 each month but spend around Rs 18,000 to cover the costs of cow-maintenance, cattle feed, and fodder. So, practically we earn only Rs 12,000 per month,” Thakor said. “This is not enough to run a family. I work as a primary teacher and my brother does odd jobs.”

Political factor

In Gujarat, control of the state’s milk ecosystem is not only a matter of dairy economics but it also has a political aspect.

This starts at a structural level. Each cooperative, right from the village level to the apex body, has two arms — one political and one administrative.

Each cooperative holds elections and elects politicians as chairpersons, while the administrative set-up is run by a team of experts and officials.

According to a senior member of the cooperative, any political party with control over Amul stands to reap electoral benefits in around 93 constituencies.

In February, Vipul Patel, BJP’s Kaira district chief, became the chairman of Amul Dairy after winning the election to the cooperative.

Kanti Sodha Parmar, a former Congress MLA from Anand who joined the BJP after losing the assembly polls in 2022, was elected as the vice-chairman in the same Amul election.

“Amul cooperative is a movement for us. We were and will remain self-reliant,” Patel told ThePrint. “Our mandalis (cooperatives) work in the interest of the nation. Price increase was a necessity, but Amul does not revise price for profit.”

Source : The Print April April 12th 2023 by Madhuparna Das (Edited by Asavari Singh)