Amul, the local and biggest FMCG brand in India, is in an aggressive expansion mode. Its hunger for growth well beyond the home state of Gujarat is both natural and disturbing.

For some state cooperatives in the south, and now increasingly in Madhya Pradesh, Amul’s aggressive expansion into their territories has become a source of political friction. Even as its ambitions trigger political storms, Amul’s plans to procure milk from outside Gujarat serves as a reminder to other states to get their cooperatives in order and pay their dairy farmers well.

Jayen Mehta, the managing director of Amul who assumed office in January, spoke in a LinkedIn post recently about promoting two new multi-state cooperatives, besides forming 200,000 new dairy cooperatives in half a million “uncovered” villages.

Amul, the brand owned by the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation, was the result of Operation Flood launched in the seventies as a strong dairy cooperative from Gujarat. Today, its annual turnover has surpassed Rs 72,000 crore ($9 billion) and India’s most successful dairy cooperative procures 30 million litres of milk every day.

As a brand, Amul today is ahead of global giants Unilever, Nestle and others in the country. So why is Amul entering other states where local cooperatives already exist?

Mehta was unavailable for comments.

Experts said despite Operation Flood and the focus on building strong, state-level dairy cooperatives, many states could not develop them. The most obvious example is Uttar Pradesh – it is one of the largest milk producers but the state has not been able to develop a strong, state-level brand.

Instead, smaller brands have cropped up all across UP. A dairy sector veteran, who declined to be identified, said UP’s dairy cooperative has an office and pays salaries to the staff but the cooperative structure of sourcing and processing milk has collapsed due to “politics.”

Along with regional dairy brands, milk in UP is sourced by the National Dairy Development Board, the owner of Mother Dairy, and GCMMF (Amul).

The cooperative dairy movement similarly weakened in Maharashtra as many profitable federations were usurped due to political ambitions.

In such a scenario, strong and state-level brands could be developed in Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. After Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu follow in the pecking order of milk procurement in the country, making them lucrative for a large dairy federation like GCMMF.

The dairy veteran said that about 9-10 years ago, Amul began venturing into states such as UP, which had traditionally weak dairy cooperatives, offering attractive prices to local farmers to procure increasing quantities of milk.

As a part of this strategy, Amul announced plans on April 5 to supply milk and curd in Karnataka. The announcement came just about a month before the assembly elections and led to widespread protests across the state and provided the principal opposition party, the Congress, a tool to mobilise pro-Kannada sentiments.

In any case, a recent amendment to the Multi-State Co-operative Societies Act, making the merger of two state cooperatives easier, had already been making several political parties and some cooperatives edgy.

Despite several attempts, Karnataka Milk Federation managing director BC Satish declined to comment on the matter.

Staunch opposition

On its website, KMF claims to be the apex body for the dairy cooperative movement in Karnataka and the second-largest dairy cooperative in the country. KMF says it procures the largest quantity of milk in south India and also accounts for the largest quantity of milk sold in the southern states under the Nandini brand. KMF procures milk through 16 unions in the state.

Why did Karnataka mount such fierce resistance to Amul’s plan to sell liquid milk and other products across the state?

T Nanda Kumar, former chairman of NDDB and former food and agriculture secretary, said, “Amul reportedly gets an indirect subsidy from the Andhra Pradesh government for procuring milk from some districts in the state. And when procurement was possible, the company obviously needed a market to sell this milk. Amul announced entry into the liquid milk market (into neighbouring Karnataka) but just before state polls in Karnataka and ran into a political storm.”

A similar fate awaited Amul in Tamil Nadu.

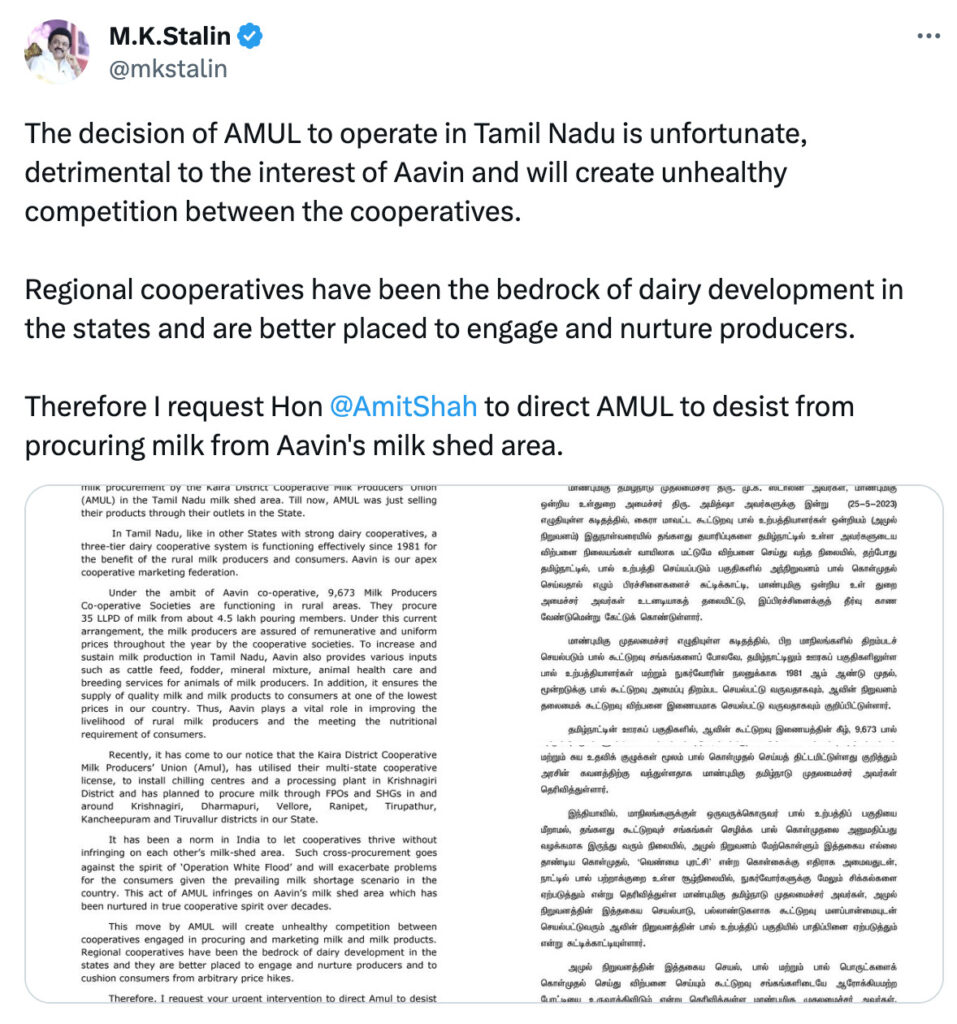

Chief minister MK Stalin wrote to cooperation minister Amit Shah, asking Amul to stop procuring milk from Tamil Nadu. Stalin referred to the norm of letting cooperatives thrive without infringing on each other’s milkshed area.

“Such cross-procurement therefore goes against the spirit of ‘Operation White Flood’ and will exacerbate problems for the consumers given the milk shortage in the country,” the chief minister said.

Tamil Nadu’s Aavin cooperative procures 3.5 million litres of milk per day from about 450,000 members.

Nanda Kumar said Tamil Nadu and Karnataka oppose Amul’s procurement “because that would mean their respective state cooperatives could lose access to adequate quantities of milk and this, in turn, would lead to an increase in the retail price of milk. This, naturally, then becomes a politically sensitive issue.”

However, another dairy sector veteran said there was nothing wrong in Amul wanting to procure milk from other states.

Better prices

“Amul already procures milk from several states where it pays far better remuneration to farmers than local cooperatives. Why should farmers outside Gujarat not get better prices for milk?” this expert wondered, dismissing the concerns of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

Nanda Kumar said that not just Amul, even Nandini sells milk outside Karnataka – in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

“But unlike Amul, it procures milk only in Karnataka, where there is a state subsidy. This is the reason for Nandini liquid milk prices being far lower than in other states,” he said.

The nub of the current political friction then seems to be milk procurement by federations from other states, not so much the sale of milk or milk products by these “outsiders.”

The latest to protest against Amul’s entry is the opposition (Congress party) in Madhya Pradesh. The party’s allegation – that Amul’s entry would “kill” the local milk brand Sanchi – is more or less along the lines levelled by Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

As the political storm over milk procurement rises in poll-bound states, perhaps it is time for their respective federations to improve processes, prices and bring in more efficiencies in the distribution of liquid milk. Or else, one of the best organised and most profitable milk federations, GCMMF, will continue to be a threat.

Source : Money Control June 09th 2023