Despite differences in farming systems, the carbon footprint of dairy products is similar among the major exporting regions, and most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions originate on the farm in the form of methane, according to a new report from Rabobank, outlining some of the reduction strategies available, including those left untapped.

ON-FARM EMISSIONS

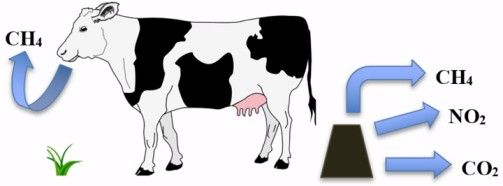

At the farm level, combined methane emissions from enteric fermentation and manure account for approximately 75% to 85% of direct on-farm emissions. The remainder is largely made up of nitrous oxide, primarily related to soil management and manure storage and application. “This suggests that the feasibility of successfully implementing mitigation measures in large exporting regions is comparable, despite differences in environment, climate, and agricultural practices.”said Richard Scheper, a dairy industry analyst at Rabobank.

However, for dairy processing companies, this means that the majority of their emissions are in scope 3 and beyond their direct control. As such, measuring and reducing these emissions can be difficult, given the complexity and number of players in the value chain, he noted.

SCOPE 1, 2 AND 3 EMISSIONS

As reported by the GHG Protocol, scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources; Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from purchased power generation; and Scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions that occur in the reporting company’s value chain.

In the case of a dairy processor, scope 1 emissions would come from processing raw milk in its processing plants. Scope 2 emissions would come from energy purchased for processing. Upstream scope 3 emissions would include scope 1 emissions from the dairy farms where the milk was purchased (methane emissions on the cow farm) and downstream scope 3 emissions would result from, for example, transportation and the disposal of waste from dairy products. .

MULTIPLE LAYERS OF COMPLEXITY

However, the difficulties are not limited to measuring and reporting scope 3 emissions in the dairy value chain. Reduction targets vary in alignment, ambition, and scope. In practice, this means that stakeholders along the value chain are exposed to different targets, according to the report.

“This situation creates multiple layers of complexity. Dairy companies want to set targets as they are coming under pressure from buyers to reduce their emissions, but the lack of alignment between national government and industry standards increases complexity, which in turn could hinder the rate of progress . In the absence of a common national guide, many people Businesshave set their own requirements and objectives“.

GHG REDUCTION MEASURES

The review identifies GHG reduction measures that are being introduced, some of which are in late stages of development or are currently being used in the dairy sector:

INCREASED EFFICIENCY AND PRODUCTIVITY

Efficiency gains have been a major factor in reducing on-farm emissions, according to Rabobank.

“Historic efficiency gains have been achieved through a combination of improvements in genetics, feed efficiency and nutrition, agricultural practices and animal welfare, contributing to higher milk yields and lifetime production per cow and lower replacement rates. In the Netherlands, for example, this contributed to a 35% decrease in carbon intensity per kilogram of milk between 1990 and 2019.

“As time and knowledge advance, these gains and efficiency improvements will also contribute to future reductions in GHG emissions intensity, but to sustain this progress, a significant amount of on-farm management skills is required. ”.

FOOD ADDITIVES

In addition, food has been highlighted as a relevant source with considerable reduction potential. This ranges from reducing losses in the field and on the farm, to improving and maintaining the quality of feed when it is grown and stored, to changing feed rations for dairy cows.

CASE STUDY: BOVAER

Much of the research has focused on the use of feed additives and their ability to reduce methane emissions in cows, analysts said. In recent years, several of these feed additives have entered the market or have reached later stages of development.

“Bovaer (3-nitrooxypropanol) is a synthetic feed additive produced by the Dutch company DSM that suppresses enzymes in the cow’s rumen so that less methane is generated, which could reduce methane emissions from enteric fermentation in cows. milkmaids by 30% without affecting milk productivity. pilot based.

“Bovaer has been investigated in more than 50 peer-reviewed scientific studies and is already licensed and available for use in more than 40 countries, including EU member states, Brazil, and Australia. The reduction potential varies according to the culture system. [Its potential in more intensive, controlled, and (seasonal) indoor farming systems appears to be somewhat higher].”

In practice, the use of such products will increase operating expenses at the farm level, Rabobank said. Although he hopes that these types of inhibitor additives will be incorporated into compound feed in many countries.

SEAWEED

Seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) has potential shown to reduce methane emissions by up to 90%, according to the review.

However, scaling up aquaculture to produce seaweed commercially can be challenging, and the long-term effects on cows are still unknown, the Rabobank team said.

GENETICS

Advances related to genetics have contributed indirectly to reducing emissions on farms through efficiency gains, but also show potential as a lever to reduce emissions more directly by raising cattle based on breeding values for low methane emissions. .

“The indicators show that significant variations in enteric methane emissions are likely to exist between breeds and individual cows of similar breed within the same herd.

“Through the exploitation of natural genetic variation in dairy cows for methane emission traits, breeding plans could offer a cost-effective emission mitigation opportunity. However, research is ongoing and further analyzes background the interaction between breeding goals for environmental traits and breeding goals for economically important traits, such as fertility and productivity.”

MANURE MANAGEMENT

Another mitigation opportunity is through manure management (storage and application) and the adoption of anaerobic digesters, which can reduce manure emissions, the authors said.

“Digesters are used to prevent gases from escaping from manure lagoons and reaching the atmosphere, so that they can instead be used for different purposes, such as fuel or renewable electricity. However, such facilities in an agricultural setting are capital intensive and are generally complex systems to operate, making their feasibility challenging for farmers.

“Possibly, numerous measures related to manure management and storage are more (cost) effective in large-scale and confined farming systems.”

While levers such as efficiency and productivity gains, manure management, and feed additives offer strong mitigation opportunities in theory, they vary in technical abatement potential, as well as in the rate of adoption and current commercialization, which can make it difficult to predict its overall reduction. potential in the coming years, the team warned.

“Probably the biggest obstacle to reducing on-farm dairy emissions is not the technical potential but rather the feasibility of adopting mitigation practices. Some mitigation levers require little or no investment. Conversely, others have great potential for theoretical reduction, but also require large upfront capital expenditure or increase operating expenses, which restricts the rate of adoption.”

OBSTACLE REMOVAL

According to the report, steps should be taken to increase the momentum for emission reductions in the dairy industry:

Alignment between government and industry goals is required to overcome layers of complexity, but at the same time, the dairy industry must fully endorse the need to accelerate GHG emission reductions. “By raising ambitions and targets, the industry has already taken the first stepsin this direction”,Schper said.

However, to gain momentum in on-farm mitigation lever adoption rates, farmers must also be incentivized by the industry, through options such as carbon tokens or premiums, in addition to the price of milk. “If mitigation does not gain momentum, the dairy industry could face the risk of government-imposed mitigation regulations that could be capital intensive or even include herd reduction,“, the analyst concluded.

Source : Delicious Foods Jan 21 2023