The India visit of the Australian trade minister in February 2022 has expedited the early harvest trade deal between both countries. An interim agreement which is expected in about a month’s time would be a major leap towards the signing of a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA) between India and Australia later this year.

In 2020, India was Australia’s seventh-largest trading partner and sixth largest export destination. The two-way goods and services trade between the countries was worth $24.4 billion. While India’s export basket to Australia majorly comprises petroleum products, medicines, polished diamonds, gold jewelry and apparel, Australian exports to India include coal, liquefied natural gas (LNG), alumina and gold. There is a huge demand for Australian premium alcoholic beverages and wines, health supplements, cold-pressed juices and trans-fat-free products in India.

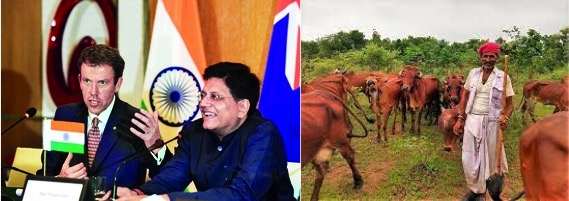

The trade ministers of India and Australia stated in a joint press meet that the sensitivities of both countries will be ‘accommodated and respected’. It is likely that Australia will not seek market access for dairy, beef and wheat which are sensitive sectors for India. Earlier this year, the Commerce Ministry of India had indicated that the interim agreement would focus on labour-oriented sectors like textiles, pharmaceuticals, footwear, leather products and agricultural products, and ruled out the inclusion of dairy and agriculture items.

This statement underpins India’s commitment to protecting its agriculture and dairy sectors, which was one of the reasons for its exit from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations, back in 2019. Indian dairy farmers, cooperative societies, and trade unions have taken a strong stance against the opening of sensitive sectors such as dairy and agriculture to the Australian giants.

The Indian dairy industry is the largest globally with milk production of 198.4 million tonnes in 2019-20. It provides livelihood to a large number of people and is dominated by milk cooperatives and small and medium-size dairy farmers, who face challenges towards achieving economies of scale in their operations. Dairy is not considered a separate enterprise in most rural households. Instead, it is well integrated with the farming system. Dairy not only supplements the agricultural incomes of farmers, but also provides a regular income and helps them overcome financial crisis during the off-season and thus, a valuable asset.

Approximately 35 percent of the dairy sector is organised in India with more and more private companies investing in developing an efficient milk procurement network, and marketing liquid milk and value-added products. The National Dairy Development Board projects a demand for milk and milk products at a pan-India level to reach 266.5 million metric tonnes in 2030.

Out of the total milk produced in India, 48 percent is consumed in the rural areas and the rest is marketable surplus for consumers. Despite being the largest producer, India’s share in the global milk trade is small. India exports dairy products to the United Arab Emirates, Bangladesh, the United States of America, Bhutan and Singapore. Skimmed milk powder accounts for 30 percent of total dairy exports. Butter, butter oil, cheese, ghee and buttermilk also form a part of the export basket. India imports (as well as exports) buttermilk, curdled milk, cream and kephir from Australia. Milk non-concentrated, cheese of all kinds, milk and cream powder are also among the dairy products imported from Australia in 2020.

The Indian dairy industry supports around 70 million rural households, which consist of mostly small and marginal farmers. The milk cooperatives, dairy farmers, and trade unions have opposed Free Trade Agreements with milk surplus economies such as Australia and New Zealand. Assuming that a lowering of tariffs may lead to dumping of cheap imported products and resultant disruption of the domestic dairy industry, several industry spokespersons have taken a stringent position against the opening of this sector.

The majority of large dairy importing nations across the world have applied various tariff and non-tariff measures to protect imports. The European Union, for instance, has not granted export clearance to Indian dairy plants under the pretext of veterinary control, levels of antibiotic and pesticide residues, etc. Even Australia permits only retorted products to be imported. While countries like the EU and USA give massive export subsidies to their dairy farmers, in India, no such support is provided to dairy farmers, making them uncompetitive in global trade.

The government has assured the dairy farmers that it will protect their interests. At the same time, the possibility of giving greater market access, by reducing tariffs or other import restrictions, to select agriculture and dairy products that are neither produced nor consumed in great quantities domestically, has been kept open. This is a sensible step, considering the growing domestic demand and consumer preference for premium, high value processed products. Furthermore, this can also be seen as a window for structural reforms to make the sector more competitive.

These reforms, particularly in supply chain management, are crucial and should comprise enhancing the quality of cattle feed, procuring quality milk, instituting rigorous quality controls, and cold chain management to increase shelf life. All with huge investment opportunities.

As per the projections on dairy demand in India, it is evident that production needs to be increased to meet the domestic demand. There is also need for investment in educating and training dairy farmers, and providing better infrastructure for the collection, transportation, and processing of milk to augment milk productivity and improve the quality of processed milk. Foreign investment, including that in agriculture and dairy services, can be sought for cold chain establishment, distribution and marketing.

It is also important to remember that foreign dairy players in the country prefer partnerships with local entities and avoid backward integration of direct procurement from farmers. Such backward integration could have benefitted our dairy farmers a lot. Another step could be to move forward and lower tariffs on dairy products not produced in India or those having high domestic demand. The rise in disposable income and preference for high protein diets has created a consumer base for such niche products. These steps may be small, but would provide a significant change in the dairy landscape of India.

Source : The Daily Pioneer, March 10 2022 (Vidyadharan is Fellow and Swati Verma is Research Associate, CUTS International, a global public policy think-and-action-tank on trade, regulation and governance. The views expressed are personal.)