On a busy day, about half a million people pass through New York’s Times Square, a big tourist at-traction known for its innovative advertising and digital billboards. On Sunday, October 8, a campaign titled ‘Be More Milk’ went live there. Targeted at youngsters, this 15-second message has been play-ing out 20 times an hour and 480 times daily. What’s cool is that it is an initiative run by Amul, one of India’s most well-known brands. The Amul advertisement is at the Nasdaq MarketSite.

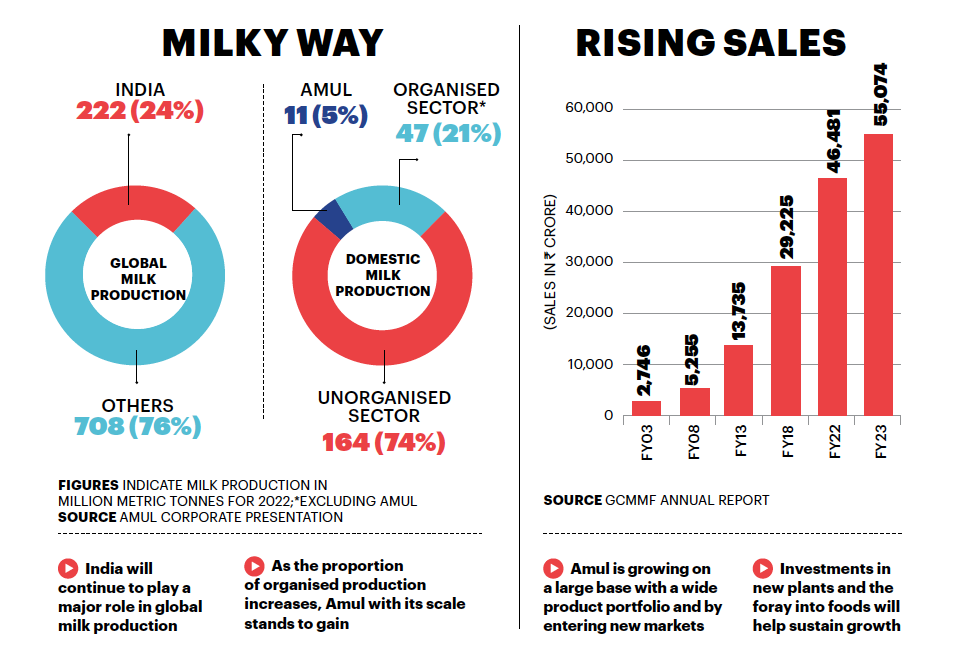

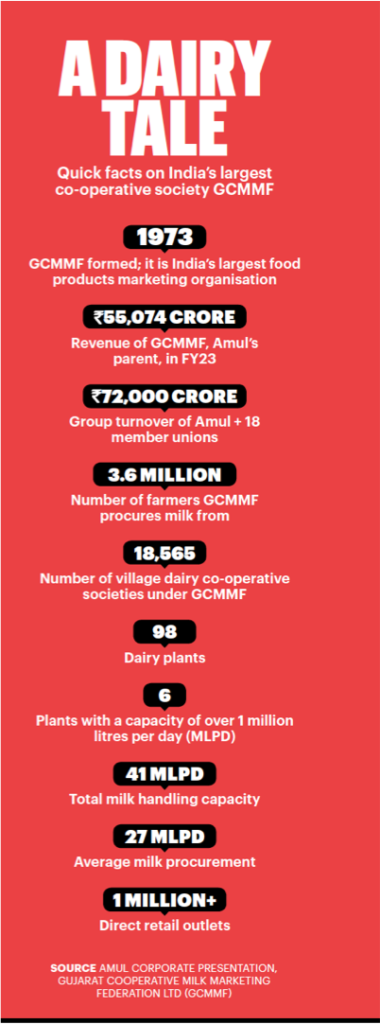

It will run for four weeks and is expected to strengthen the base of the Indian dairy major’s jour-ney into foreign markets, although it pushes the cause of milk more than of Amul. The dairy major wants to go beyond the Indian diaspora. And it has the muscle: for FY23, Gujarat Coopera-tive Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), which owns the Amul brand name, reported a turnover of `55,070 crore, an increase of over 18 per cent on the previous year. The target for FY26 is `1 lakh crore. The group turnover, or the unduplicated sales (this includes those of member unions) of all products under the brand Amul, exceeded `72,000 crore last financial year. Milk and milk products still account for 96 per cent of GCMMF’s revenue. But it wants to change this by aiming for scale in new businesses that fit nicely into the Amul supply chain and its closeness to farmers. For one, the co-operative behemoth is hungry for organic food.

There is a smile on Jayen S. Mehta’s face as he pops in a gud kaju katli, a sweet made of jaggery, cashew and milk. “It is quite addictive,” says the 54-year-old Managing Di-rector of Amul. Mehta joined in 1991 as a freshly minted graduate of the Institute of Rural Management Anand (Irma) and succeeded R.S. Sodhi this January.Amul’s decision to move beyond dairy into foods has been interesting and perplexing. The two are very different businesses with unique challenges. India is the world’s top producer of milk, which is also its largest agricultural product. “At `10 lakh crore, milk is larger than wheat, paddy, and oilseeds put together,” he says. Amul is a big brand, and the trust it enjoys “is our currency”. If the farmer-owned co-operative can churn a perishable product such as milk into a portfolio of products, it reckons it can do better with farm produce. “We can do it with wheat and potatoes, for instance.

Making a frozen potato snack is logical, but core agricul-ture was never a part of our thinking,” explains Mehta.Everything changed when the management began looking into the word “organic”. Amul told farmer-co-operatives: go organic, and we will find you the market. “To consumers, it is a product promise free of chemicals. If we get it right, we can be in every item of the kitchen,” he says confidently. In a moment, some staff members walk in with what is already there in the market—whole wheat atta, basmati rice, chana dal, toor dal, rajma—with the plan to be in turmeric, spices, sugar and jaggery. Amul will buy directly from farmer-producer com-panies or FPCs, farmer-run companies offering scale to buyers.

“This is the direction we are taking. It’s not as if organic has not been there but the trust is missing, and we have a right to win,” says Mehta. The question is, why didn’t Amul enter the business earlier? He says now is the time to build scale. Plus, things have changed after the Covid-19 pandemic. “Not many people know we are the largest probiotic brand in the world. We sell 3 million litres of pouched chaas every day, and a few months ago, we decided to go probiotic with the entire lot.” Even the Amul choco bar is probiotic. The success with probiotics—microbes added to enhance the nutritional value in dairy prod-ucts—has made Amul more confident. This conversation with Mehta in his Anand office, a little over an hour from Ahmedabad, is not just about rice and pulses. It is around 7:30 p.m., and he asks if I would like to sample some of Amul’s new products. Soon, the table is filled with sweets, chocolates and a surprising array of beverages.

Amul sells over 35 varieties of sweets (for a long time, it sold only shrikhand), and the team hands me a box of marzipan. At `250 for eight pieces, the almond and chocolate confectionery makes for a perfect combination before you are offered a frozen kheer. The festive season will see the launch of a dodha barfi. Mehta insists I try cold coffee in a glass bottle. At `100, it fills the premium space in coffee after the suc-cess of the more affordable Kool in a can. “We source the ingredients and use filter processing at scale. If it works, we will move it across plants.”Another initiative in the premium piece is Amul Ice Lounge, where Amul sells only 15 flavours of ice cream (no other Amul product will be visible here), and that includes English Apple, French Caramel, Italian Fudge and Butter Pecan. These are the most popular versions from each country, and there are five lounges across Ahmedabad, Pune and Jaipur. Sold by the scoop, each is priced at a competitive `200.

According to him, this is a complete reorientation of the dairy business with the limit “being only in our minds”.Mehta pauses before getting back to organic. “It is not a rich man’s game; we want to democratise it. Middlemen make the money, and my assurance to the farmers is on all crops, be it organic or inorganic,” he explains. That means Amul will buy out the complete produce and can offer a large portfolio to consumers. “I can make a paneer paratha using my organic atta. It is about selling the concept of organic and not the range.”Speaking of the link to farmers, Amul set up a plant in Gujarat to make French fries with a 100-tonne-a-day capacity. Today, it runs to full capacity and a large part is exported to Japan. Likewise, high peanut production saw Amul launch peanut butter variants.

“Amul’s marketing has been down-to-earth, simple and focussed on the product. They have never used celebrities, and the quality value has spoken for itself,” says D. Shivakumar, Operating Partner at global private equity firm Advent International. Amul’s co-operative background has laid a strong foundation where farmers get the highest price, and consumers are charged the lowest. “MNCs have a year-on-year growth target on margin percentage plus absolute delivery, but Amul has worked on getting the right return,” he explains. He says brand success in food categories comes from managing the supply chain apart from upholding product integrity and quality. “Amul does that better than the MNCs,” he declares.

The dairy potential in India is unlimited. Both co-operative and private sector dairies have a role to play. According to Srideep Kesavan, CEO of the `3,250-crore Hyderabad-based Heritage Foods, there is a big opportunity since per capita consumption of milk products in India is around 350 gm, less than half of many Western countries. “Packaged milk consump-tion will continue to grow strong, driven by urbanisation,” he says. Regarding value-added dairy products, Keswan is clear that thanks to its versatility, the long tail of dairy products is seeing rapid penetration and sharp growth is inevitable. “We see it in the case of a range of dairy drinkables, ghee, paneer or sweets amid a clear shift towards a cleaner and packed option.”

Regional focus is a competitive moat in dairy, as Rashima Misra, co-founder of Bhubaneswar-based Milk Mantra recognised before starting-up in the east in 2010. “The market opportunity stood out—there was no large dairy player, consumers had limited options with almost no product, quality or functional differentiation with the available brands, and with an untapped farmer base, it made eminent sense to lay the foundation for something new,” she says.To her, a presence in pouched milk is important since it has a lot of stickiness with the consumer. “Sri (the other co-founder) and I chose to own and differen-tiate every aspect of the value chain, starting with the farmers to consumers.

Our strategy is to have a tight product portfolio to ensure focus on maintaining our mass premium pricing position with strong margins.” Amul has 122 products ready for launch and 50 at various stages of ideation. Mehta sees millet as a big opportunity. “We can do an organic version like a wafer chocolate made of millet and jaggery or an ice cream cone made of millet. It can easily be moved across the country,” he says. Taking a product category mass is not an unknown territory for Amul.Anand Kumar Jaiswal, Professor of Marketing at IIM Ahmedabad, picks out how Amul democratised ice cream consumption and became the largest player. The current strategy, says Jaiswal, is to make Amul a food brand and not just a dairy brand. “They want to reduce their overdependence on dairy and look for ways to diversify their portfolio. Besides, it presents opportuni-ties to use excess capacity across the value chain,” he ex-plains. For instance, deep freezers where retailers store ice creams now have French fries and frozen parathas. “Amul can benefit from using the same vehicles and align its cost structure effectively. It also helps them beat seasonal fluctuation of a category like ice cream.” Amul has gone about foods in a calculated manner, with product launches spread over at least a decade before getting into top gear now.

The success of choco-lates is another interesting example. Chocolates were seen as expensive, but Amul launched a 150-gm bar when the standard size was 40 gm or, at best, 80 gm. Then, Amul went for dark chocolates, which are viewed as a healthy option. Today, Amul has become a domi-nant player in chocolates with almost no advertising. Jaiswal believes the approach in organic foods will be similar to that in ice creams. He says the supply of organ-ic foods in India is still limited with incumbents needing to invest a lot in developing the market. “For Amul, the connect with farmers plus the ability to produce at scale could lead to lower prices. Besides, there is no big player in organic today, presenting an opportunity to democra-tise it.” Per a report by research firm IMARC Group, the organic foods market in India was pegged at $1.3 billion last year with the potential to reach $4.6 billion in 2028. Shivakumar believes the expansion into foods will be difficult. “Milk is perishable and that led to the full ecosystem wanting Amul to succeed,” he says.

By contrast, pulses and grains are not perishable in the same way with established distribution channels built over the years. “Neither one farmer nor one region grows everything. For example, ITC buys tobacco in Guntur and wheat from elsewhere. That means the backend synergies at the farmer’s level are not obvious, though the capabilities are fungible in a sense,” he says. The approach will be to take the Amul brand name and trust to the farmers. “It will be over a decade, and they will finally get it right, but one should not expect an overnight success.” Milk is a good source of protein, but there is also a need for whey (the liquid that remains after milk has been curdled), which is a quality protein.

Many years ago, when Mehta was running Amul Dairy (the Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers’ Union), he spent time understanding whey but realised a lot of money was needed to reprocess it. But a solution was needed. Typically, the need for protein is a gm for each kilo you weigh or 60 gm daily for someone who stands at 60 kg. “With milk, dal and buttermilk, you will get a maximum of 30 gm,” says Mehta. Since importing protein is arduous, Amul launched a high-protein lassi and buttermilk by dissolving whey powder. “The taste of the buttermilk is different but about con-scious consumption.

Our lassi is sugar-free.” K.S. Narayanan, an independent food advisor, says Amul’s protein move “is an excellent initiative consid-ering the way the markets are evolving”. Indians, he says, have a diet deficient in protein. “With rising per capita income, the quality of food consumption has un-dergone a big change and additional protein in mass-consuming products like dahi (curd) or buttermilk is a good way for consumers to make it a part of their diet.” Mehta shows the artwork for a protein shake lassi. “We can launch a protein ice cream or high-protein milk, cereals, snacks, yoghurt or chocolates. Even a protein chocos is possible, where it is an FMCG prod-uct, but I come with the ingredients,” he says.

One challenge that Amul has faced is the availability of its products at retail outlets. Buying it in Anand is one thing, but that’s not the case in other centres. This is where e-commerce has been a big help, and Amul, with its Shop Amul online store, offers a substantial part of the range. “I do this with the existing ware-house system and sell at MRP.” Nitin Karkare, Vice Chairman of FCB Ulka Ad-vertising, which has handled a substantial part of the Amul account for over three decades, says they have got it right on the basics like superior product, better packaging, value for money, consistency in communication and smartly using social media. “There is the patience and staying power to build scale over time. As they transition from dairy, the playing field will not be restricted to just India, and the power of the Amul brand can be leveraged exponentially,” he says. Rahul daCunha, MD of daCunha Communications, which created the iconic Amul girl and runs the funny topical ads, says, “Consistency is the heart of brand equity. Speaking of the girl, we keep her constant be it the polka dotted dress or the blue hair and that cannot change,” he says. The girl never pokes fun but will only nudge you with a smile. “People see her as a symbol of continuity in the midst of so much change.”

BEING SAVVY

Cricket continues to be the biggest event in India. Amul decided to be the official sponsor not for India but for Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and South Africa in the ongoing ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup. “It does not have to be expensive if you are good at deal-making,” says Mehta with a grin. Last year, they were the regional sponsors for the Portugal and Argentina football teams at the FIFA World Cup.

Again, given the vast base of users on social media, Amul operates in 14 languages, including Sanskrit, Sindhi and even Arabic for the Middle East, a key market. From a spend perspective, Amul’s outgo on advertising is less than one per cent of its sales, while FMCG biggies easily spend upwards of 8-10 per cent.

Combine that with the part on doing good as a cooperative, and the model becomes formidable. Private sector rivals say Amul has no pressure to deliver profits as it is a co-operative. But Shivakumar says, “Many food MNCs were unprofitable for the first two decades in India. Amul does not get enough credit for helping Indian farmers, and it is hard to think of many co-operatives as large as them worldwide.”

The plan is to invest `5,500 crore in new projects. Mehta says it will include a new AmulFed dairy (the manufacturing unit of GCMMF) in Rajkot, new plants across Pune, Ujjain, Kolkata, and Goa, and the expansion of eight ice cream plants. Amul is also creating beachheads in south India. Referring to the controversy surrounding the Nandini brand, Mehta makes it clear that there is a good relationship, and Amul ice cream is manufactured at Nandini’s plants. Amul is getting into what could be the most critical phase of its growth. Normally, growth on a large base is difficult. Amul is pushing that mindset to the limit.

Source : Business Today Nov 12th edition