The Amul example shows how the co-operative model has created an enabling environment for milk producers. Himachal Pradesh, where the new CM has promised an MSP for milk, should take a cue

After the Congress won the Himachal Pradesh elections, chief minister SS Sukhu promised a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for milk. “We will streamline milk procurement, offer to buy 10 litres from every family, set up chilling plants and resell the milk in the market at a subsidy: we will recover costs by levying a cess on the sale of liquor.”

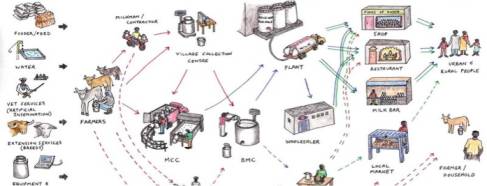

The public associates dairy with Amul (Anand Milk Union Limited), managed by the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd (GCMMF). So, how does the milk collection, processing and production work, under the cooperative model, and can the State, as in the case of the promise made by the Himachal Pradesh CM, be an alternative?

Every village supplying to GCMMF has a village dairy co-operative society (VDCS) collection centre, where a procurement supervisor receives milk from producers. Every VDCS has a secretary and chairman. There is no limit on the quantity of milk a producer can sell. Every collection centre has an automatic milk testing machine where the weight, volume, fat and percentage of SNF (milk solids that are not fat) of the milk received are checked. The centre displays the price offered per litre for given fat and SNF percentages. When milk is received, these parameters appear on the screen, and the amount payable to the villager is known immediately. The amount payable is directly transferred by the milk union to the milk producers’ bank accounts.

Milk at the centre is collected by a tanker and taken to a chilling centre. A bigger tanker takes the milk from the chilling plant to the dairy where it is processed.

The above stages might vary in districts. Milk tankers may visit some VDCSs twice a day. The milk is tested in a laboratory at the plants. Once cleared, the milk is unloaded, processed and treated. The Amul website sums up the chain—member producers (16.6 million in India, 3.6 million in Gujarat), VDCS (185,903 in India, 18,600 is Gujarat), district milk unions, or DMU, and the state milk federations (such as GCMMF).

According to the National Dairy Development Board’s Annual Report 2020, “Cooperative milk unions covered about 1,96,114 village dairy cooperative societies with a cumulative membership of 17.26 million milk producers.” The DMU provides VDCS with subsidised cattle feed, veterinary services, animal breeding services, rural health schemes and a team of veterinary doctors to assist milk producers. It also gives dividends, bonus and additional price differences.

The DMUs make products for, say, GCMMF, under the brand Amul. Marketing and last mile distribution of products is done by GCMMF. While there are dairy co-operatives in most states, none is as popular as Amul.

The surplus from the sale is shared at three levels (after all costs) with milk producer members. The first at the village level or the VDCS, the second at the milk union level (DMU) and third, at the GCMMF level. In FY22, Banas Dairy, a GCMMF DMU, distributed a surplus of `1,650 crore to 3.71 lakh milk producers. This money, in addition to what milk producers received for milk sold, is distributed at the end of the financial year, enhancing rural incomes. Note that milk production depends on various factors, including season, milch animal, etc.

Now, returning to the proposed scheme in Himachal Pradesh, the cost of collection would be higher, due to the terrain and the yield lower because the region has mainly cows. Thus, the surplus at village level would be lower. Fixing a limit of 10 litres per family—procurement at MSP—could motivate milk producers to find ways to beat the limit. Experience has shown that government involvement in activities like purchase and processing breeds corruption and inefficiencies. In 1971, the Maharashtra government introduced a Cotton Monopoly Scheme with the avowed aim to capture the whole economic value for the farmer, from growing cotton to selling finished cloth. It proposed to do this by helping farmers get a fair price for their produce, make available unadulterated cotton to consumers at reasonable prices, produce textiles and distribute bonus (profit on operations) to farmers.

In a 2006 article, I had examined why the scheme did not lead to prosperity or prevent farmer distress. Since each cotton procurement area was managed by a grader, this functionary became a big power centre, extracting bribes from farmers. Two, the state government had financial difficulties sustaining over-payments to farmers. These problems could arise in Himachal, too. To breach the limit of 10 litres per family, families could, on paper, show they are two households while they are just one—just like in Punjab, where people are applying for one more metred connection to benefit from the scheme of 300 units of free power.

Conversely, in Gujarat, the government focused on creating an enabling environment. Should any state government venture into milk collection, production and sale or leave it to a time tested co-operative model is a question worth pondering over, Cross-subsidisation (cess on liquor) encourages inefficiencies and rarely works.

Source : Financial Express Jan 5 2023 by Sanjeev Nayyar