At the recently held 75th foundation year ceremony of the milk cooperative Amul, home and cooperation minister Amit Shah advised the leadership to not restrict the benefit of the movement to its 36 lakh farmer shareholders.

He noted that successful cooperatives should create an online platform to globally market the produce of non-dairy farmers and specifically gave the example of organic farmers.

While being an admirable vision statement, it seems to be a big ask and reminds us of a small ask some six decades back.

The due credit for Amul’s foray into chocolates should go to C. Subramaniam, the agriculture minister of India from 1964-67, who is the often-forgotten member of the troika comprising Nobel Laureate Norman E. Borlaug and well-known agricultural scientist M.S. Swaminathan, who are together considered the architects of the Green Revolution. Having understood that Indian cocoa farmers were deprived of a fair price for their produce due to the existence of a monopolistic buyer – Cadbury, Subramaniam suggested to Verghese Kurien that Amul should enter the chocolate world. That was a small ask because chocolates had a milk connection and could be distributed by the cold chain network that had been set up for butter.

Thus, in the late 1960s, Amul started working in Kerala and Karnataka with areca nut and cocoa farmers to form them into cooperative societies. This movement eventually became an organisation in its own right in 1973, which we now know as CAMPCO – Central Arecanut & Cocoa Marketing and Processing Co-operative Limited – which in itself is a Rs 1,800 crore enterprise now. The cocoa beans were then transported to Anand, Gujarat and processed to make chocolates in a plant that was set up with the help of Nestle.

Nestle? Kurien and Nestle’s relationship was legendary. In the 1950s, condensed milk was a popular form of consumption and storage of milk in cities, as milk was in short supply and refrigerators not as ubiquitous. In 1956, Kurien went to the Nestle headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland on their invitation along with a message from the then commerce and industry minister Manubhai Shah, that Nestle should manufacture condensed milk in India from Indian milk instead of importing milk powder and sugar. The discussion got heated and Kreeber a co-MD of Nestle Alimentana eventually said that the process of making condensed milk was extremely delicate and could not be left to ‘natives’. Kurien took umbrage and stormed out of the meeting. Amul initiated R&D and after two years, made condensed milk on its own.

Verghese Kurien. Photo: William Yardley/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

The government then banned condensed milk imports and Nestle had to finally seek government permission to set up a plant for condensed milk in India. Manubhai Shah insisted on a letter of introduction from Kurien. Thus, Kreeber and the management of Nestle had to troop down to Anand. He was duly shown the condensed milk plant and he profusely apologised for the earlier incident. Kurien eventually gave the letter, and as legend has it, extracted milk chocolate technology and Nestle knowhow to set up a plant in Anand as quid pro quo.

Nestle represented the blue blood of the chocolate world. While Theobroma Cocoa, food of the gods, had been consumed in Latin America since the Aztec and Mayan times in liquid form, it was the making of the milk chocolate bar that brought it into every person’s reach. Spanish colonisers got chocolate to Europe in 1528 from Mexico and it spread across the continent to reach England by the 1650s. It took another 200 years and an industrial revolution to make the first chocolate bar. J.S. Fry & Sons of Bristol, England made the first solid chocolate bar in 1847 and some 100 miles away in Birmingham, John Cadbury made his eponymous solid chocolate bar, by 1849. It took yet another two and a half decades for milk chocolate to be made, which made chocolate more palatable and pocket friendly. That development took place in Vevey, Switzerland.

Vevey too had become a hub for chocolate factories by the early 1800s. Francois-Louis Cailler started his factory in 1820. Kohler started his factory in 1830. Cailler’s son-in-law Daniel Peter started his factory in 1867, around the same time that his neighbour and friend Henri Nestle started his infant milk food business. Henri Nestle had a hand in the development of milk chocolate in 1875 by Daniel Peter, providing him with condensed milk.

Eventually, all three of them – Cailler and Peter and Kohler – became part of Nestle in 1929. Lindt initially worked at Kohler’s and then set up his chocolate factory in 1879, establishing his own brand. One of Lindt’s initial customers, Jean Tobler, opened his factory in 1899, which eventually launched ‘Toblerone’. Thus, by the turn of the 19th century, the Swiss had taken the lead in milk chocolates, helped in no small measure by a burgeoning dairy industry and the Swiss cow, whose bell later caught the imagination of Indians in the popular movie Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayege.

Cadbury made milk chocolate only in 1897. Its defining milk chocolate – Cadbury Dairy Milk – came out in 1905. Fry merged with Cadbury in 1919. Elsewhere in Europe, Cacao Barry (France) and Callebaut (Belgium) got into the chocolate business in 1911, while Godiva started in Belgium in 1926.

Across the pond, Milton S. Hershey developed his own formula for milk chocolate and made the Hershey bar in 1900. Frank Mars started his milk chocolate bar in the 1920s and his son, Forrest Sr, started M&M in 1940. Meiji in Japan launched its milk chocolate in 1926.

In the absence of non-disclosure agreements then, because milk chocolates were an innovative product, these food tech startups relied on secrecy and family ties to keep their formulae from being copied. Spying on each other was rampant as portrayed in Roald Dahl’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Even today Ferrero (started 1946) doesn’t allow cameras or tours in its factory. More than a century later, these brands and companies continue to dominate the $106 billion chocolate market.

Table 1: Global top 100 candy companies 2021

| Rank | Company Name | Turnover (in $ billion) | Base Country |

| 1 | Mars Wrigley (Conf Div includes gums) | 18 | The US |

| 2 | Ferrero | 13 | Italy |

| 3 | Mondelez (Cadbury) | 11.8 | The US (UK) |

| 4 | Meiji | 9.7 | Japan |

| 5 | Hershey | 7.9 | The US |

| 6 | Nestle | 7.9 | Switzerland |

| 7 | Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprungli | 4.5 | Switzerland |

| 8 | Pladis | 4.5 | UK |

| 9 | Haribo | 3.3 | Germany |

| 10 | Ezaki Glico | 3.1 | Japan |

Source: Global Top companies for 2021

Like Ford, Facebook or Google, the credit for Nestle’s success should go as much to its geography and its timing, as to management. Nestle (started 1867) and the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company (started 1866) were competitors in the infant food and condensed milk business and merged in 1905. The same year, they added milk chocolates to their existing product lines. After World War I, women began entering the workforce because there was a shortage of men. Lactogen was launched in 1921 to cater to the feeding needs of infants left at home. The Great Depression made Nestle work on another innovation: Nescafe instant coffee, launched in 1938.

Condensed milk was used as army ration during World War I and chocolates and Nescafe during World War II, which not just brought bulk orders to Nestle but also popularised the products across the world. After World War II, there was a spike in birth rates (the Baby Boomer generation). This led to a further increase in the consumption of infant milk food. By 1958, when Kreeber and Kurien met, Nestle was already a multinational behemoth. Wrangling the technology for milk chocolate from this behemoth was a veritable coup.

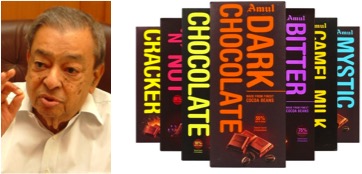

Amul chocolate wrappers. Photo: Provided by authors

By WWI, most of the imperial powers made chocolates without growing cocoa beans. They were sourced came from colonies, usually using slave labour. While the era of colonialism is over, issues of equity and fairness still remain in the chocolate trade.

Even as the world consumes chocolates worth $106 billion annually, the countries producing cocoa bean get only $8.6 billion – less than 10% of the consumer dollar. In fact, 60% of the worlds cocoa bean is produced in Ghana and Ivory Coast. Farmers growing cocoa beans there struggle for an income of $2/ day and are too poor to eat chocolates that are made from their crops. About 80% of the world’s cocoa, from the top five producing countries, flows to Europe and North America. The inequality in trade is complicated by the presence of middlemen known as trader-grinders. Out of the 4.6 million tonnes of annual cocoa beans production, just three companies – Cargill, Olam and Barry Callebaut – control 60% of the flow. Eight companies control more than 90% of it.

Amul chocolates, if it had achieved what was planned, would have been a shining beacon of fair trade and equity in the world of chocolates. India would have been a self-sustaining region for chocolates, with the farmers owning the brand and getting 80 paise of the consumer rupee. Half a century later, there is a trend of Fairtrade chocolates in the western world. European brands like Divine chocolates, in which a Ghanian farmer’s cooperative Kuapa Kokoo has a 20% stake, represent heart-warming initiatives.

Amul launched Amul Milk Chocolate in 1973 in 40 gram and 80 gram packs. It initially faced a lot of problems as the Swiss milk chocolate formula ensured that chocolate melts at 35 degrees centigrade, the temperature of the human mouth. Considering the average temperature across the country, the product would melt before it could be consumed. Amul tried to work around it by packaging the chocolate in a silver/golden foil, a pioneering move in the industry, but it didn’t bring in the desired results. The cat taught the tiger everything, except how to climb the tree. In 1982, the Asiad Games and the advent of colour television in India also saw the memorable advertising campaign: ‘Amul Chocolates: A gift for someone you love!’

In the liberalised 90s, the Amul management felt if it wanted to be serious about chocolates, it should spin off the business as a separate company and put in place a youthful and dynamic CEO who would function independently. There was a realisation that the skill sets required in the chocolate business are entirely different from the dairy business. They also planned to get an international partner for a joint venture to build on the marketing DNA and provide input support to farmers.

Around 1993, after evaluating the various international players, Amul approached Hershey’s, currently an $8 billion chocolate enterprise, as its sensibilities were similar. Milton Hershey not just pioneered milk chocolates in the US but also sold them at affordable prices so children could enjoy them. The factory town of Hershey had many facilities like schools and amusement parks for workers and their children. Because he and his wife could not have children of their own, they set up an industrial school for orphaned boys in 1909. After his wife’s death in 1918, Hershey gifted his entire fortune to the Hershey School Trust.

Beyond the gamut of marketing and brands, the joint venture also aimed to help the farmers improve their yields and make new chocolate production technology available to the company.

But liberalisation left Amul with a deeper existential question regarding its core milk business. Could a farmers’ cooperative take on the behemoths of the dairy industry, as they enter India? Could it fight a marketing intensive chocolate battle with international chocolate giants at the same time? Amul’s management felt that while dairy is an integral and substantial part of Indian agricultural income, cocoa wasn’t.

Amul took the strategic decision not to focus on the chocolate business and concentrate its resources and management on dairy. Thus, Amul not just moved out of the geography of Gujarat to launch milk in metros and big cities of India but also launched value-added products like ice cream, curd, flavoured milk, cream and so on.

In a sense, Amul chose to lose the chocolate battle to win the dairy war.

Today, the chocolate market in India is consolidated – as it is elsewhere in the world. About 80% of the Indian retail market of Rs 11,260 crore is captured by four multinationals – Mondelez (Cadburys), Nestle, Ferrero and Mars. Amul’s share is just 3% and CAMPCO’s is around 2%. More than half of India’s requirement of cocoa beans are imported.

Yet, with a less than desired success level, the cooperative movement has left its mark in the Indian cocoa space. In the past three decades, Indian cocoa bean prices have on average been 5.2% higher compared to international prices. Indian farmers also managed to escape the cocoa bean price crashes in 2016-17 and 1999-2000.

Source: www.dccd.gov.in; Directorate of Cashewnut and Cocoa Development, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Government of India. Table in Annexure 1.

Interestingly, Amul used the art and technology of chocolate making to develop value-added products like ice creams, shakes, syrups and flavoured milk to meet the aspirations of a generation of consumers. Today, Amul uses more cocoa products in its ice creams and beverages than to make chocolates. Amul continues to buy the bulk of its requirement from CAMPCO, which it helped establish in 1973 and whose factory it later helped set up for a princely sum of Rs 1. But each time one takes a bite of Amul’s choco bar ice cream or sips an Amul chocolate flavoured milk, they are reminded of the possibilities that could have been.

It is inevitable that in the coming decade, chocolate consumption in India will explode exponentially. India is also geographically blessed to have regions where cocoa can grow (20 degrees north and south of the equator). Now seems to be an appropriate time for Amul to get back in the chocolate business. May the powers that be at Amul and the Government of India say, “I too had a dream!”

Source : The wire Nov 18th 2021,B.M. Vyas was the managing director of GCMMF Ltd (Amul) from 1994 to 2010. He also was part of the team that launched chocolates in 1973. Manu Kaushik is a management consultant and a former GCMMF Ltd senior executive